Bottled water. Just about every one uses it. It’s handy, it generally tastes good, and it’s costing the environment dearly. Americans drink over eight billion gallons of bottled water every year – about 28 gallons of bottled water per person, says the American Beverage Association, equal to $11 billion in bottled water sales.

Bottled water. Just about every one uses it. It’s handy, it generally tastes good, and it’s costing the environment dearly. Americans drink over eight billion gallons of bottled water every year – about 28 gallons of bottled water per person, says the American Beverage Association, equal to $11 billion in bottled water sales.

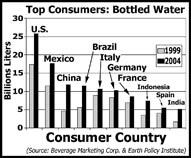

Wall Street has a name for the bottled water market: Blue Gold. It’s right in there with oil and diamonds. The Blue Gold market has been growing at about $1 billion annually, according to the Beverage Marketing Corporation; a rate 75 to 85 percent greater than any other beverage product.

How good is bottled water? The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulates bottled water quality, and the Environmental Protection Agency sets tap water standards. But there are so many brands out there, and such a large volume being bottled, that it is difficult to test and track all of these products. In fact, the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) conducted a four-year study to find out how the FDA is doing and reported that “one-third of the bottle water tested contained levels of contamination which exceeds allowable limits†under state or FDA guidelines or standards.

The claim of bottled water sellers is you’re getting better water. Some cite events like the 1993 Cryptosporidium protozoan outbreak in Milwaukee as reason enough to have bottled water (about 403,000 people got sick), and, in Door County, contaminated wells that impact restaurants and individual households (a noroviral infection plagued 239 patrons and 18 employees at the Log Den in 2007). Each of these types of outbreaks has been followed up with sampling and testing to determine causes and remedies. Overall, these outbreaks are rare, and in and of themselves do not seem to justify a waterlogged bottled water market.

Where does bottled water come from? It can be sourced from wells, springs, glaciers, or purified (filtered or treated) supplies. The FDA says about 75 percent of bottled water comes from groundwater sources, but the remaining 25 percent is from municipal sources. That means some companies are filling their plastic bottles with municipally supplied tap water. In essence, they’re selling your water back to you, since you’ve already paid for it through local taxes.

I did a brief survey of bottled water I could find in some local Wisconsin grocery stores. This turned up no less than 87 companies, of which 60 were from the United States, and 22 were bottled overseas. I could not determine a source for five of them. The bottled water from the United States came from 21 states, and overseas came from 14 countries.

Consider the implications of drinking water from Romania or Fiji or British Columbia or Nepal when we live next to Lake Michigan. The Great Lakes hold nearly 20 percent of the world’s fresh water supply. Interestingly, eight of the companies bottle water in California and ship it nationwide; California is commonly stricken with water shortages, yet they are exporting considerable amounts of it even as pipelines are being contemplated to import water from other states. This is not a sustainable situation, and it is enough to make one want to drink local water.

But what is the real cost to the environment of bottling water? According to the Earth Policy Institute these plastic bottles are rarely recycled (only 10 – 15 percent nationwide), and the results translate into more litter and larger landfills. Those are a couple of the visible “downstream†impacts. But the process of getting bottled water to you has other hidden impacts. Consider this: over 900,000 tons of polyethylene terephthalate (PTE) plastic is used annually to make the plastic water bottles, and this requires an estimated 17 million barrels of oil (www.valleywater.org).

One example of hidden impacts tracks the CO2 emissions created from the manufacture of PTE bottles for one company on a small south Pacific island. The bottles are manufactured in China (producing 93 grams CO2 per bottle), and then the empty bottle is transported to Fiji (producing 4 grams CO2). Once filled with water the product is shipped to the United States (producing 153 grams CO2). This totals 250 grams of CO2 added to the atmosphere for every bottle of water brought from the island to the U.S. (source: P. Paster at http://www.Treehugger.com). This does not include the water processing impacts, and that it takes approximately three to five liters of water to make a one-liter plastic bottle. All told a bottler requires nearly seven liters of water to produce and deliver one liter of bottled water.

Furthermore, transportation costs require an estimated 500,000 gallons of oil (12,000 barrels; enough fuel for 80,000 homes or 30,000 cars for a year), and all other manufacturing costs consume another one billion gallons of oil annually. This might not sound like a lot of water, but consider the eight billion gallons (30.3 billion liters) of bottled water we consume. This translates into nearly 56 billion gallons (212 billion liters) of water that is used and consumed just for the bottled water industry. These are a lot of “billions,†but the point is we are consuming a lot of water to make bottled water, when in most cases our municipal water supply is very good and, in fact, preferred.

The cost also hits your pocket book. Remember, you are already paying for municipal water or your own well water, and this typically costs pennies on the gallon. My local survey identified bottled water that sells for $2.05 – $12.80 per gallon, with an average of $6.56/gallon. The average American spends between $100 and $200 per year on bottled water when their tap water in nearly all cases is just as good.

What is being done? Many states are requiring plastic bottle recycling. Provinces like Ontario are charging commercial and industrial water users to help pay for the cost of managing public water sources. San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom has banned the use of city funds to purchase single-serving bottled water. States like Michigan are limiting the production and sale of Great Lakes watershed sourced water as an exportable commodity. Closer to home, the local municipalities and sanitation, health and conservation departments are working hard to ensure high-quality safe water supplies. Contamination events are taken seriously and improvements to our water supply are being made.

What can you do? There are a number of proactive measures you can take to reduce your consumption of bottled water and work toward sustainable water usage. These include:

- Use a recyclable water container (camping bottle).

- Use tap water to refill your recyclable water container.

- Test your water supply (Department of Natural Resources can provide home test kits; contact their drinking water specialist).

- Ask your municipal and county officials about the quality of our public water supply.

- Do not contaminate groundwater (remember: what goes on the ground goes in the ground).

- If you have a septic system, ensure that it is not leaking.

- Conserve water usage.

- Keep track of your carbon footprint!

For more information in Door County contact: John Teichler, Door County Sanitarian; Brian Forest, Door County Soil & Water Conservation Department; Rhonda Kolberg, Door County Health Department; Laurel Braatz, Water Specialist – Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. On a state level contact the DNR and Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey (in Madison). On a state and national level contact the U.S. Geological Survey and the Environmental Protection Agency.