It’s called the cliff, the Great Arch, or simply the ledge. It’s a 650-mile curve linear cliff exposure of up-ended Niagara Dolomite that stretches through eastern Wisconsin and Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, arcs around the top of Lakes Michigan and Huron, and on through Niagara Falls. In geological circles it’s known as the Niagara Escarpment, and it’s one of the most significant features on the Door Peninsula.

It’s importance was recognized this year by the Wisconsin Legislature, which proclaimed 2010 the “Year of the Escarpment,†and the Door County Board of Supervisors, which recognized it in May.

The escarpment is not a continuous ridge, but intermittent exposures broken by valleys and bays. The Niagara Dolomite rock that forms the escarpment reveals a fascinating story of geology, natural history, and human endeavor. The story starts with oceans, and culminates in rocks and forests and settlements. Like a book, the fossils and textures in the Niagara Dolomite are akin to words on a page that geologists read to decipher the past. These pages are part of an intricate story that helps put our lives in context with the natural history of eastern Wisconsin. This context can help us protect our natural areas and better manage our resources and protect water supplies.

If we could get a bird’s eye view of the early Paleozoic world (those chapters in time between 450 and 350 million years ago) we would find a series of small basins or connected shallow seas from the Ordovician, Silurian and Devonian periods. The shallow sea that gave us the Niagara Dolomite is called the Michigan Basin. At that time Wisconsin was underwater and situated at a latitude of 16 degrees south of the Equator. It was a time of coral seas inhabited by reefs of colonial corals, exotic bug-like trilobites, lily-like crinoids, and tentacled torpedo-shaped cephalopods.

As the Michigan Basin’s floor sunk, more sediment was deposited, and the resultant rock tipped up like the rim of a saucer all around the state of Michigan, exposing soft shale under the dolomite. The dolomite would form a ledge as the shale weathered out. The saucer’s edge would ultimately become the Niagara Escarpment – but only after hundreds of millions of years of erosion. Plate tectonics would carry this patch of earth north to our present latitude.

There is no record in Wisconsin of the hundreds of millions of years that existed between the formation of the dolomite and the much younger glacial tills and outwash deposits. This was largely the time of the dinosaurs, which thrived in the seas when marine incursions flooded the land, and tromped around on the dry or forested uplands. But even then the land was being uplifted, and that means everything was eroding – especially dinosaur bones. We know this about the dinosaurs and erosion by comparing neighboring geologic environments and reconstructing the continents through time. In eastern Wisconsin the Niagara Escarpment would have existed further west than today’s location.

Two million years ago the Earth experienced an ice age. Great sheets of ice accumulated in Canada. There were at least five significant ice accumulation regions that helped the Laurentian Ice Sheet grow more than 6,000 feet thick. The ice on Greenland is the last vestige of that era. The thick ice moved very slowly across the landscape, scraping off the soils and rubble, and carving into the softer rocks of Canada and the northern United States. The glaciers acted as sculptors, putting the finishing touches on a deeply eroded land. The Green Bay Lobe of the Laurentian Ice Sheet further carved the eroding edge of the Niagara Dolomite. Some valleys were filled, others scoured, and the meltwater filled our lakes and groundwater aquifers.

Two million years ago the Earth experienced an ice age. Great sheets of ice accumulated in Canada. There were at least five significant ice accumulation regions that helped the Laurentian Ice Sheet grow more than 6,000 feet thick. The ice on Greenland is the last vestige of that era. The thick ice moved very slowly across the landscape, scraping off the soils and rubble, and carving into the softer rocks of Canada and the northern United States. The glaciers acted as sculptors, putting the finishing touches on a deeply eroded land. The Green Bay Lobe of the Laurentian Ice Sheet further carved the eroding edge of the Niagara Dolomite. Some valleys were filled, others scoured, and the meltwater filled our lakes and groundwater aquifers.

The abundance of water continued dissolving the dolomite to create caves and karst. Karst is a geologic and topographic terrain that results from a rainwater solution of limestone and dolomite. This dissolving process creates holes and caves, some of which collapse and open to the surface to make sink holes. Door County is a bit like a block of Swiss cheese – full of holes – from this karst formation process. Geologist and Door County caver Bob Bultman frequents one such cave, the Horseshoe Bay Cave, which is exposed in the escarpment south of Egg Harbor. Bultman notes that the cave follows the karst and joint features deep into Door County. “After storms it runs like an underground river,†he said.

By the end of the glacial era, some 10,000 to 12,000 years ago, the Niagara Escarpment stood as a stubborn reminder of the Earth’s legacy – born from warm equatorial seas and sculpted by continental glaciation.

The First Peoples in Wisconsin gazed from this rocky loft about that time, maybe as early as 14,000 years ago. They brought early tools and knowledge of the transitional climate and environments immediately following the glacial times. They would have seen the ice sheets retreating northward, benefited from the abundant life fed by the incredible melt waters, and hunted mammoth and other surviving species.

These earliest people may not have settled here, but those that followed did, and some found sacred sites along the Niagara Escarpment. Dr. Robert Jeske, Professor of Anthropology at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, Department of Anthropology, has been studying Wisconsin’s effigy mounds. Important ones occur at the Nitchke Site just west of Lake Winnebago within the Niagara Escarpment region. Findings from these sites, which date from A.D. 600 to A.D. 1200, indicate these were ritual spaces for the early inhabitants of Wisconsin.

“The lack of significant architecture, and prevalence of wild rice, nuts, deer and fish suggest these people moved around a lot – they were hunters and gathers,†Jeske said.

They came together periodically to build mounds to bury their dead, and make alliances and conduct trade. Corn became important after A.D. 1000, and this led to the agriculture-based communities of the Oneota and other tribal groups.

The escarpment also represents a natural barrier between the oak savannas and prairie. Native Americans burned portions of the savanna to establish prairie lands for agriculture, but the fires seldom reached east of the Niagara Escarpment, which acted as a natural firebreak.

The Europeans who settled in Wisconsin after 1634 found abundant woodlands as a source for lumber and game for food. In time, the industrious ones mined the extensive sand and gravel deposits and quarried dolomite for building materials.

Today, the habitats surviving on the escarpment are fragile and of great scientific importance. Biologists have identified 241 rare species and natural communities along the escarpment in Wisconsin. Ancient White and Eastern Red Cedar trees grow on the exposed vertical faces and on top of the cliff zones. In 1996, researcher Doug Larsen discovered a 1,200-year-old Eastern Red Cedar on the Brown County segment of the escarpment. Gary Fewless, curator for the University of Wisconsin–Green Bay (UWGB) Herbarium Center, reports finding dead trees that were 1,800 years old. These cedars represent some of Wisconsin’s truly ancient forests.

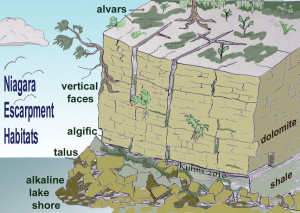

The Niagara Escarpment is host to five important habitats:  1) exposed vertical faces, 2) shallow-dipping cuesta slopes above the cliff that host thin-soil alvars and bedrock glade communities, 3) algific zones cooled by air flowing  through fractures in the dolomite at the cliff base, 4) rock talus also accumulates at the cliff base, and 5) alkaline rock shores develop where the escarpment meets the lakes, bays and rivers (see diagram next page).

through fractures in the dolomite at the cliff base, 4) rock talus also accumulates at the cliff base, and 5) alkaline rock shores develop where the escarpment meets the lakes, bays and rivers (see diagram next page).

Examples of these habitats can be seen in Door and Kewaunee Counties at a number of county and state parks, including Door Bluff Headlands County Park, Peninsula State Park, White Cliff Fen and Forest State Natural Area, Potawatomi State Park, Bayshore County Park, and Wequiock Falls Park.

Thin soils, rocky cliff faces, and rugged talus all create challenging environments for plants and animals. A variety of algae eke out an existence on the cliff by growing into the rock as much as an eighth of an inch. This rugged alga maintains about 15 percent of its biomass within the porosity of the dolomite. Other plants, such as the cedars, also cling to the vertical faces. These trees are characteristically stunted compared to the normal forest environment because they put their energy into survival, not vertical growth. Plants on the vertical faces struggle just to maintain footing, as evidenced by their gnarled character. The cliff environment provides nesting sites for birds, notably the Peregrine Falcon, and gliding birds take advantage of cliff-side updrafts. Bats and even Turkey Vultures utilize the caves and crevices in the dolomite for shelter.

At the base of the escarpment we find the algific and talus environments. Here warm air from the cliff-tops moves through joints, fractures and karst holes in the dolomite to the base of the cliff. The air is cooled on this short journey, and maintains a very localized, cool microclimate in the sheltered cliff base and talus. It is in this algific environment that scientists have discovered a number of tiny snails. One could fit a half dozen of these snails on the head of a dime. Professors Bob Howe and Jeff Nekola from UWGB’s Cofrin Center for Biodiversity found these tiny snails surviving amid the moss and ferns in an environment that mimics 10,000 year-old Pleistocene-like conditions. Twelve rare snail species have been identified, and six of these are considered glacial era survivors. The algifichabitat is restricted to within three feet of the cliff base – that’s it. This narrow zone is home to several species of salamanders and the Red Belly Snake that depend on the environment for winter survival. Howe notes that the snail habitat is destroyed wherever trails have been constructed along the cliff.

Because of these sensitive habitats many people are concerned about human activity on the escarpment, where there is a long history of building, quarrying, and recreation. Gary Fewless said at a recent

Niagara Escarpment Resource Network (NERN) gathering, “We like to stand on top of it and look at something else – views!†But, he noted, “When you cut down a cedar for a view from the escarpment what have we lost? We have to think of all the pieces.â€

The Niagara Escarpment’s importance as a recreational and educational resource remains critically important to the region. Dr. Joanne Kluessendorf of the Weis Earth Science Museum is a proponent for a strong geo-tourism industry in Wisconsin, especially along the escarpment.

“Residents can learn more about where they live, and host communities can give visitors a better experience while bringing economic benefit to the area,†Kluessendorf said.

But integrating preservation with geo-tourism requires businesses to emphasize the character of the local environment, and become active in the protection of these valuable resources. The escarpment is of international significance and, in fact, the Ontario segment is part of the UNESCO World Biosphere Reserve. Here in Wisconsin numerous local groups strive to protect the escarpment with help from the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Wildlife Action Plan.

NERN has gathered information that helps promote balanced land use of the escarpment and its resources. Mark Walter, a co-chair for NERN and Director of Bay-Lake Regional Planning Commission, said that some of the issues NERN looks into include historic and cultural resources, wildlife habitat, wind energy potential, surface and groundwater resources, and impacts from large farming operations and development projects.

Mike Grimm, the Executive Director of the Door County Nature Conservancy, reminds us that, “The escarpment, shore and wetland environments so prevalent in Door [and Kewaunee] Counties are the result of water, bedrock geology and glacial history.â€

The escarpment may technically be a cliff, but this cliff and related local and regional habitats are connected to our hydrologic, geologic and biologic systems. An impact to one is an impact to all. Sustainable practices for preserving and protecting the Niagara Escarpment are of the utmost importance today so that this natural treasure can continue to add important value to our lives here in Wisconsin.